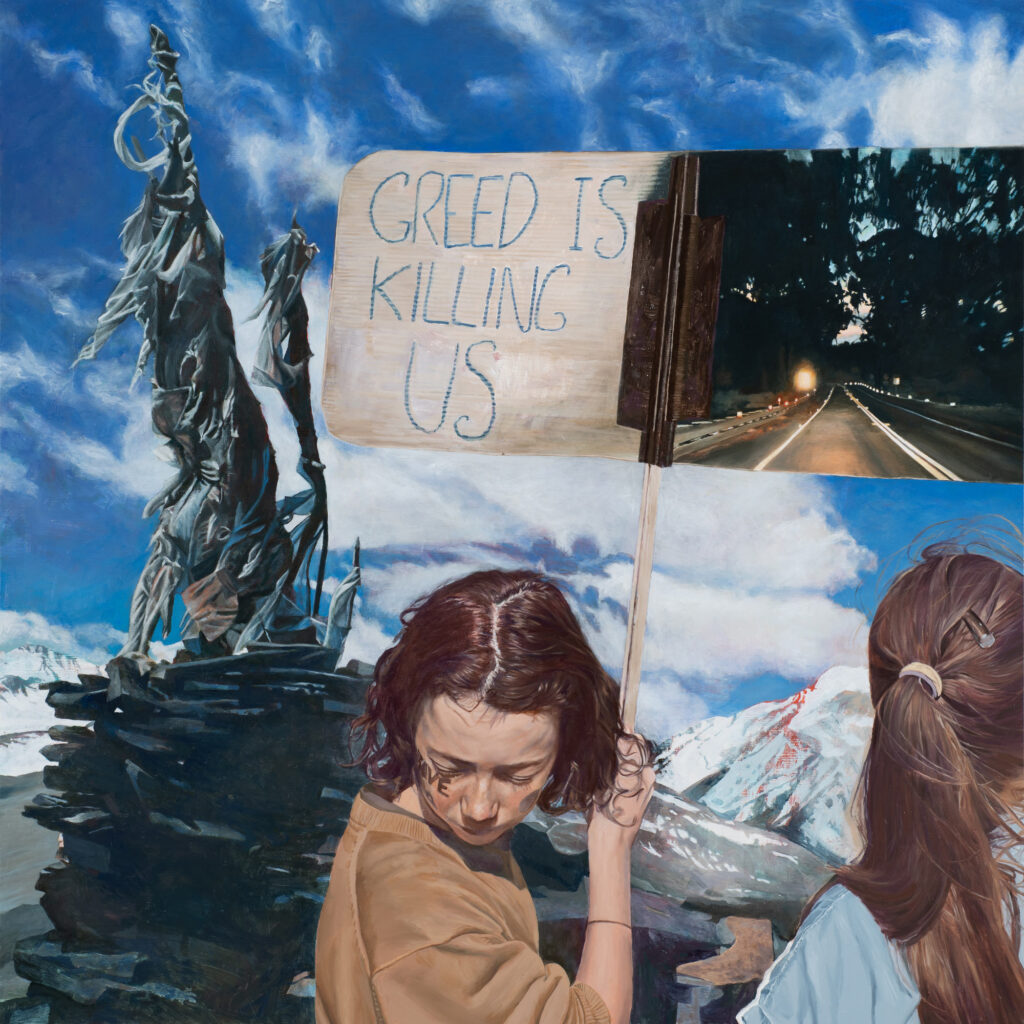

The Last Cool Skies

Thinking about art from a time of pandemic is an interesting notion, because not only is there a pandemic that has changed so much of how we behave, how we look at the world, how we associate with people and how we live our lives. But other crises seem fairly definitively to lie underneath this one. One of them, for certain, is the social and racial justice crisis that was clearly set off in its current form with the refusal of The Uluru Statement from the Heart (The Uluru Statement from the Heart’, The Uluru Statement, 2017, https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement). And then there is the equally large crisis of climate warming borne out of a war on nature; we all saw that while fires ravaged the nationas 2020 started. All of this unfinished business was entwined with the impact of the arrival of COVID-19 as the pandemic ravaged Europe, then the USA, then India.

The notion of a war at home is not new. We need look no further than First Nations Australians enduring and surviving long struggles beginning with Invasion and then the Frontier Wars. For whitefella Australians, there was palpable shock as our way of life shifted under the stress of isolation, quarantine, hard interstate borders and repeated lockdowns to stave off COVID-19. Brown and Green, living and working in regional Victoria, quickly combine compulsive listening to the State Premiers’ long news conference updates with a simultaneously hyper-vigilant but slightly benumbed turning inwards inside the walls of our workspace even though, for us, the limitations on movement are way less ferocious in regional Australia and we can walk along nearby ridges over rocky outcrops and watch a whole season’s wildflowers change for the first time in decades, with no travel and no commuting.

What surfaces from the debris of our cluttered artists’ minds in regional Victoria is that we see Australian culture once again facing its deepest, most debilitating problems: the survival of the past into the present and specifically the survival of long wars and refusal of long perspectives into the present. This is why we felt such intent anticipation of the major Australian art exhibition of 2020, NIRIN, the epochal 22nd Biennale of Sydney that so few of us eventually saw.

We had ourselves been focusing on two themes, portraying, first, the great tension between Australia’s vision of itself profoundly shaped by wars starting 100 years ago—Imperial wars fought by colonials in foreign lands, often in the unacknowledged company of First Nations volunteers—and, second, wondering about the national self-regard profoundly bent out of shape by catastrophic crises abroad and at home that disrupt such national stories through the ongoing, never-ending crises of climate warming, Indigenous reconciliation, immigration and asylum-seeking. In the process we produced in mid-2020 with Jon Cattapan a book, Afterstorm: Gardens, Art and Conflict, compiled from many voices.

At the start of 2020, we are faced with problems at the grand, double scale of climate warming’s clear arrival and a global pandemic. Both surpass the nation-state’s puny, porous borders; they are both post-national and national. Both problems are linked in the minds of artists and experts on counterinsurgency. They unfold within the glum, divisive, disruptive logic that wars at home usually exhibit. They push Brown and Green back home to Australia in early February 2020 with three hours’ notice at Singapore airport as the first of several journeys abroad were gradually cancelled. The foundation we are visiting in north India texts us to not proceed; they just can’t guarantee safety. The peripatetic travel schedules typical of the last couple of decades for all of us in the art world—and especially those of us involved in thinking about biennales—begin at first provisionally then hesitantly and finally definitively to end from late March 2020, when we cancel their flight to Sydney the night before NIRIN’s vernissage because the writing is on the wall.

In those first couple of months in 2020, the impact of COVID-19 for us artists initially meant accepting change: staying home, not travelling, working out Zoom protocol and backgrounds, checking in on family, getting tested. But we know we are tiny pieces inside big pictures. Brown and Green start on three large lockdown paintings to finish by the end of 2020, focusing on them alone. They become unbelievably detailed, but that’s not the aim. What we want to portray is the deep history of cosmopolitanism amid turbulence: mysticism, protest, wars on terror and even science. Within the details might lie a masterclass in the artistic use of cultural hybridity but something else too—can we find peace out of lockdown instability—so that is the unifying question of the first of the three big Lockdown paintings, Into the Light (2020). A compendium like that is the product of stay-at-home. They both design the composition, select the images; take on the painstaking work with fine new Japanese brushes from Hiroshima, of all places. But this is the uncontrolled expenditure of labour amidst evaporating schedules and dread.

We are painters. We are accustomed to working long periods alone in our studio at a hilltop home in regional Victoria. Working in a purposeful, solitary routine is not the same as working through an enforced lockdown. All of this leads at first to starting and stopping. The first few months of COVID pass in a hit and run rhythm of provisional work just as COVID-19 paralyzed the arts and cultural industries in general for an extended but defined period. Slowly the pandemic moment appears to be precipitating new methods of art practice, pedagogy and exhibitions in a period already in crisis but these things are still very much at a formative stage as of mid-2021.

Solutions to grand problems usually centre on accepting change. They pivot around facing up to the survival of the present into the future. Though conflict across the world has been perpetual and relentless, comprehending the pivot of big change proves hard for Australia and the world to accept, as populist debates about national climate policy have amply demonstrated. For example, 10% of Australians reported being directly threatened by the 2019-20 bushfires; about 1.8 million people were forced to evacuate homes.

The country town where Green and Brown live is ringed by forested hills; a few years ago, on a hot night they watch one lighting strike after another ignite fires in a great, real-time video-game southward arc towards Daylesford. The causal relation between human settlement, ecological disruption and pandemics is long-accepted. So, in the face of this, our hope of surviving and thriving is predicated, as it has always been, on imagining the future before it arrives and positively influencing how it is shaped. Australia has a vast scientific, political and pedagogical task, but also as yet uncharted tasks for artists and art museums. If we are to creatively respond and adapt to the current cascade of catastrophic turbulence, we must advocate the fragile emotional vision that culture and art awakens and fixes. For art vividly communicates to people the survival of the present into the future.