2009-17. Shadowlands

Shadowlands (Brisbane: Bruce Heiser Gallery, 2017). Transformer (Melbourne: ARC One Gallery, 2016). Lesson Plan 2: A Collaboration (Sydney: Dominik Mersch Gallery, 2016). Lesson Plan: A Collaboration 1 (with Jon Cattapan, Brisbane: Bruce Heiser Gallery, 2015).

In August 2016, the Vietnamese government abruptly cancelled an elaborate Australian cycle of celebrations meant to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Long Tan. There were plans for about 3,000 Australian visitors, including veterans of the battle, to converge on the site, which is a busy, working farm, not publicly accessible (we have visited, with local assistance). Celebrations unravelled in the face of a Vietnamese veto, provoking an Australian media storm about the unfairness of denying the commemoration.

By contrast, a perceptive Australian ex-Army observer, who had been stationed near Long Tan during the Vietnam War, wondered how Darwin residents would have felt if Japanese navy pilots returned for a reunion in Darwin to mark their bombing raids. He suggested a better course would be a service at the Australian War Memorial. The Long Tan anniversary shows our need to imagine others’ tragedies alongside our own and tackle, head-on, all insularity within Australian perspectives, instead respectfully advancing outlooks that portray why we all share in the state of flux and emergency that marks our period.

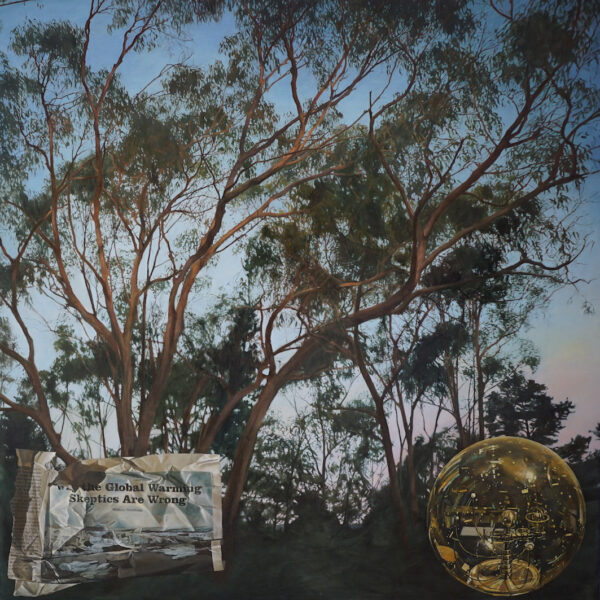

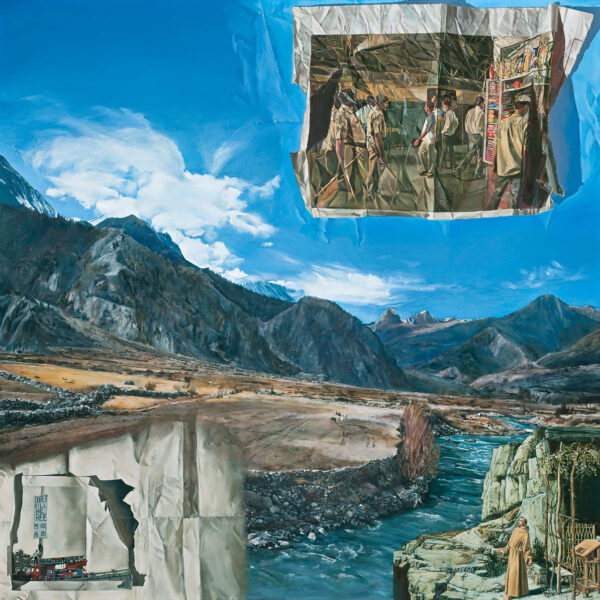

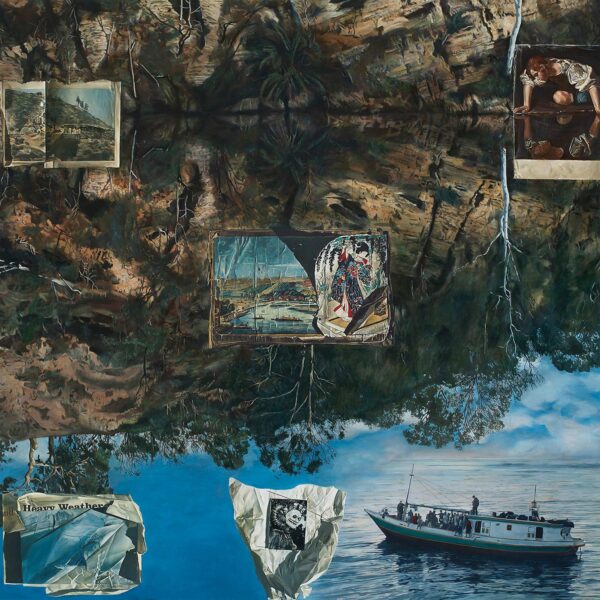

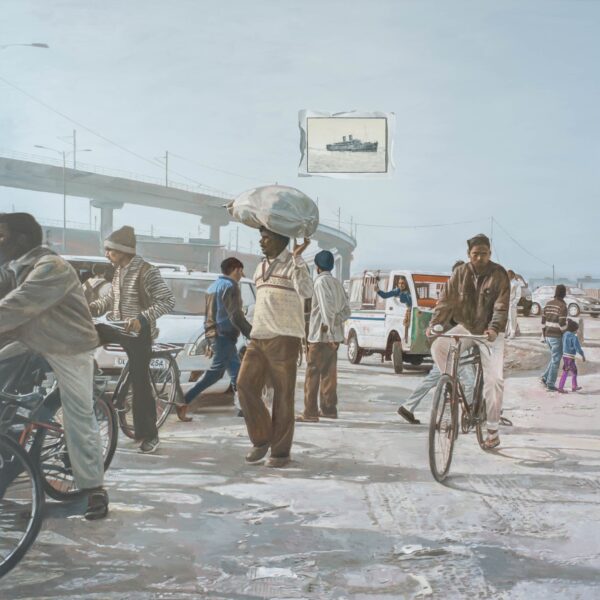

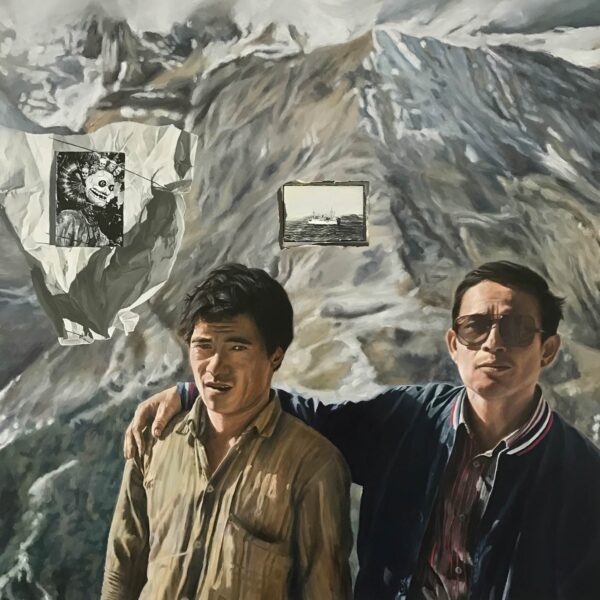

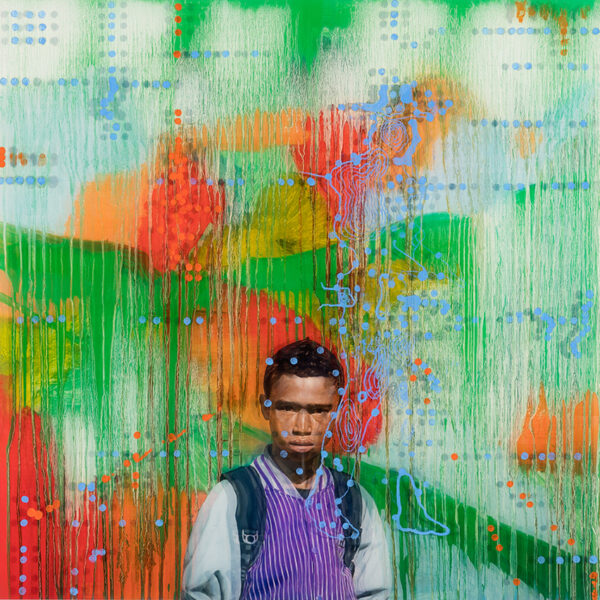

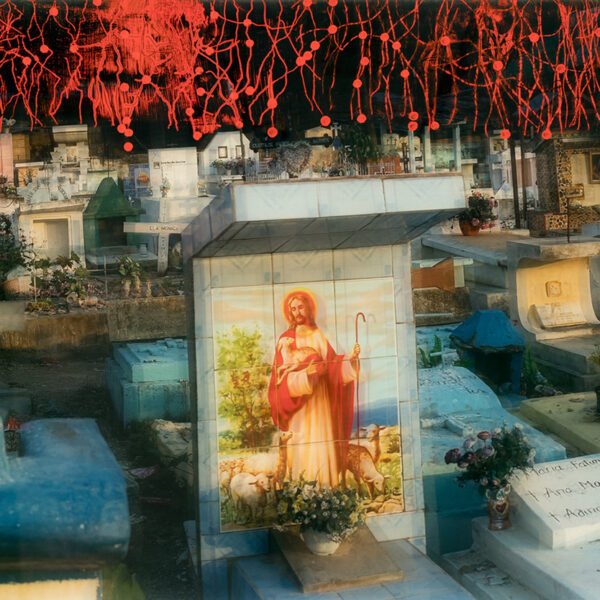

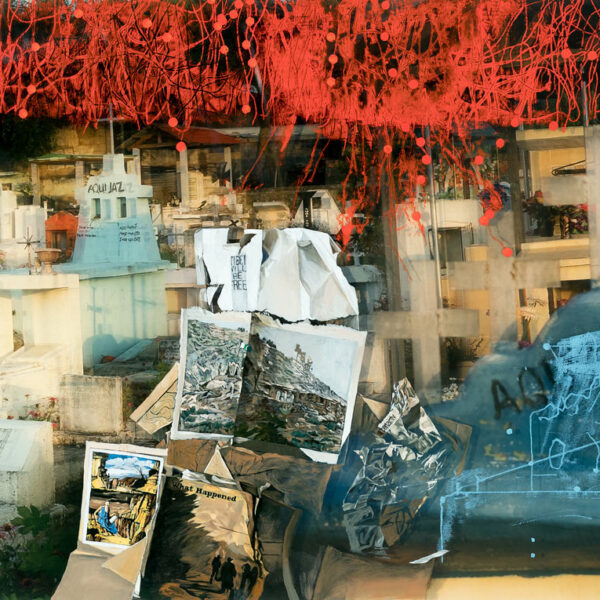

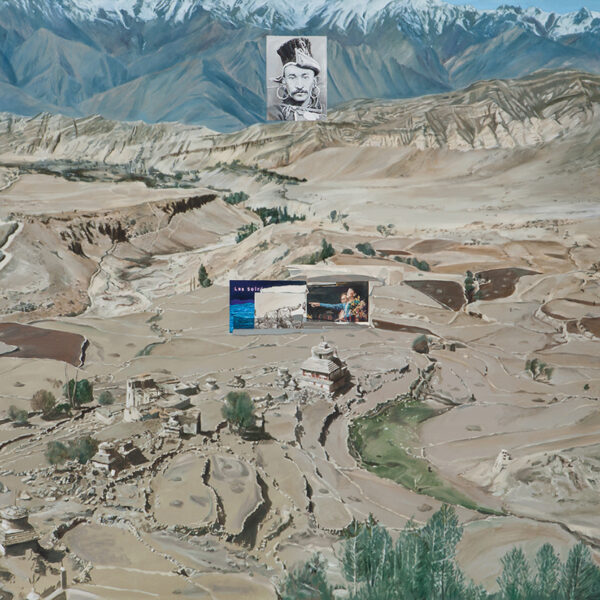

We have explored for 30 years how painting can be made a critical form of art practice in an era of reproduction. We have shown an interplay of visual symbols and images that has transcultural curiosity and meaning. In the mid 1990s we developed large paintings that placed fragmentary images from art history within aerial views of cities, ports, airports—scenes of globalisation—with fastidiously painted trompe l’oeil (hyper-illusionistic, highly skilled realist painting), inventing a contemporary version of the 19th century’s moralizing depictions of recent history. We developed in art the theories of white Australian guilt that we had explained in our book Peripheral Vision (1996), the first history of Australian postmodern art, exploring the globalization of western culture by inventing “occidentalist” images, taking the method of the tattoo, imported from Europe’s journeying to the Pacific, as a clue to layer images of journeying on top of images borrowed from the history of oil painting. Following a 1997-98 artist residency in New Delhi, we drew on Indian theories of modernity to develop an understanding of transcultural image migration that is cosmopolitan, extending this by working with other artists, first in four large art museum exhibitions with prominent New Zealand artist Patrick Pound. The next exhibitions explored the same themes, merging painting and photography in order to photographically “fix” chains of conflicting memories in large photographs on transparent film. After 2001, with the arrival on the War on Terror, our exhibitions focused on images of MV Tampa and children overboard. In a four-artist team (with Farrell & Parkin), we presented a joint show at the Art Gallery of New South Wales that toured to New York. It depicted, curator Blair French wrote, “small theatres of suspended reality, hallucinations and dreams [that] are not conditions of escape but urgent performative undertakings through which history, society and the self fleetingly come into focus” through the lens of global migration. It was consistent with this focus, then, that we were approached for appointment as Australia’s Official War Artist (2007) to Iraq and Afghanistan at the height of both conflicts. We were deployed for six weeks in combat zones and remote military bases, completing a large 33-painting commission and 14 mural-size photographs for the Australian War Memorial. Our contribution was to revise the rhetoric surrounding images of war, challenging the depictions of action previously dominating Australian war art, constructing a strongly affective sensation of bleak objectivity by apparently neutral, very large photographs of stillness, and with paintings of dust and emptiness. Through such apparent neutrality, we deliberately created a sense of clarity amidst chaotic ruination that led the viewer to understand the vast intersections of force that distinguish the appearance of contemporary war. Writer Amelia Barikin explained what this meant: “These are images about how the past figures in the present, and how it might be accessed and remembered. They are about the realisation and reconstitution of events. As such, they constitute a deeply political project.” (Amelia Douglas, “The viewfinder and the view,” Broadsheet, 38/1 (Sept. 2009), 200-205). This was the same perspective that led Pankaj Mishra to later write, in 2016, “Instead of making history, individuals find themselves entangled in histories they are barely aware of; and their most conscientiously planned action often produces wholly unintended consequences, generating more perplexing histories.” In the next project, “War and Peace” (2011-2013), we recorded with yet another collaborator, Jon Cattapan, the aftermath of conflicts in which Australia had been involved, as participant and as peacekeeper from Vietnam to Iraq, depicting massacre sites, battlefields and places of grief, loss and sacrifice as they appear now.

We have been travelling in India for long periods over the last four decades. Over this time, we have witnessed massive transformations, both positive and negative. We have seen Delhi, a city we know well and love deeply, become the most polluted city in the world. In 2012, Pankaj Mishra wrote,

For most people in Europe and America, the history of the twentieth century is still largely defined by the two world wars and the long nuclear stand-off with Soviet Communism. But it is now clearer that the central event of the last century for the majority of the world’s population was the intellectual and political awakening of Asia and its emergence from the ruins of both Asian and European empires. To acknowledge this is to understand the world not only as it exists today, but also how it is continuing to be remade not so much in the image of the West as in accordance with the aspirations and longings of former subject peoples. (Pankaj Mishra, From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia (London: Allen Lane, 2012), 8.)

This exhibition clearly consisted of images that depict the dynamics of resource shortages, climate, changing demographics, social division, conflict, and technology, all of which are already forcing changes to our national narratives, which will need to emphasize instead of security our enmeshment in complex change and the priority of equality and understanding. Art practice can at least navigate and interpret these changes.

![League of Birds LYNDELL BROWN CHARLES GREEN, League of Birds, 2015, Oil on inkjet print on linen [Diptych, each 240 x 175 cm]](https://lyndellbrowncharlesgreen.com.au/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/2015-brown-green-league-of-birds-2015-copy-q33kizafj0316sfib7a6nwx0vmgd663swbq560f1io.jpg)